Viewing city projects through a transformative lens

Urban environments present myriad challenges. Traditional urban solutions often fail to address the root causes or overlook critical aspects of a project. Avoiding preconceived solutions, identifying social challenges, understanding the cultural context, and focusing on practical considerations and challenges are essential elements for success across city landscapes. Let’s examine these urban challenges through the lens of three transformative projects in San Francisco, showcasing how understanding the problem and leveraging innovative lighting solutions can make a positive impact on a community.

Rethinking Preconceived Notions

Oftentimes, lighting designers are approached with a preconceived solution and tasked with providing technical assistance to help make those solutions work. However, preconceived ideas about lighting and its brightness must be rethought to come up with solutions that make urban areas a more inclusive and cohesive experience. For instance, floodlighting to deter crime might seem to be an effective option but can create harsh environments, ignore the underlying social issues, and cause the widening of gentrification of urban neighborhoods, ultimately proving to be ineffective.

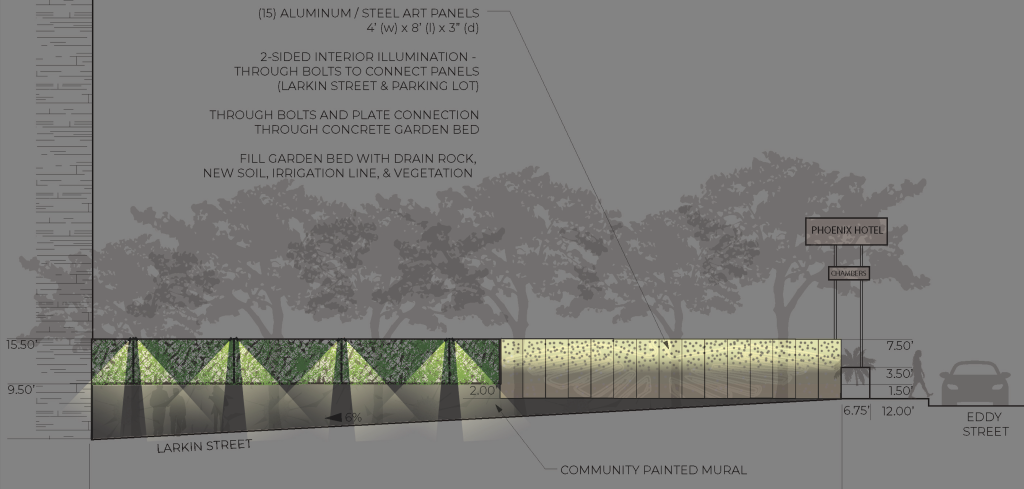

So, how can light be used effectively? Let’s start with an example of sidewalk illumination. In San Francisco’s Tenderloin District, the sidewalks at Larkin and Eddy Streets were notorious for illicit activities. As dusk fell, this dark sidewalk, with a chain-link fence and overgrown vegetation, became a focal point of activity, drawing in vulnerable populations and illegal-drug peddlers. Urban and Environmental Designer Mark Bonsignore, neighborhood business owners, and stakeholders, with the support of nonprofit organizations, embarked on a mission to solve the issue by rethinking this space from a design standpoint.

Driven by a preconceived notion, community partners proposed installing cool-colored floodlights on the sidewalk to deter undesirable activities and create a safer environment for businesses and residents. However, thanks to lighting expertise being leveraged on this project, a refined solution was reached.

The initial eyesore, which served as a dumping ground for used needles, was replaced with a Corten-steel fence, strategically featuring the logo of the adjacent Phoenix Hotel. Rather than illuminating the sidewalk, the light was strategically employed to make this new fence the primary object of illumination and, thereby, a focal point of the neighborhood.

The goal was to create a vertical illuminated surface that formed a backdrop to all the activity on the sidewalk rather than lighting down on the activity itself. The Corten-steel fence was elegantly grazed with narrow-beam linear lighting on both sides and accent lighting was applied further down the sidewalk, illuminating existing vertical foliage and forming a continued bright vertical surface reshaping the entire backdrop of the street corner.

This modest illumination project has had a profound impact on the lives of residents. Businesses across the street now attract customers who were previously deterred, and individuals residing at a nearby senior-living facility can better access public transportation at the other end of the street.

Elevating Urban Areas

Many urban areas are complex ecosystems with intertwined social challenges, such as deteriorating infrastructure, crime, and socio-economic disparities. How can designers help elevate some of these issues in a troubled urban setting? San Francisco’s Market Street, known for its vibrancy, changes after 5th Street, revealing cross streets inhabited by the city’s homeless population. Moving into 6th Street, despite its proximity to the Theatre District, the Filipino Cultural District, and the Transgender District, the area showed signs of deterioration. COVID-19 worsened this decline, closing long-standing businesses and allowing issues from the nearby Tenderloin District to spill over. Today, the area presents a stark contrast between rundown single-room occupancy units and newly built market-rate apartments.

Jessie Street, an alley off 6th Street, was particularly challenged by crime and illegal-substance sales. The Office of Economic and Workforce Development (OEWD) partnered with Sol Light Studio and Bonsignore to use light as a tool for revitalization. Rather than simply adding more light to brighten up the alleyway, a façade lighting scheme was conceived to enhance the architecture of the buildings on either side of the alley. Narrow uplights were employed to highlight the buildings and provide a feeling of grandeur, with beautiful cornices at the top of the buildings illuminated, seemingly crowning the structures. By lighting the façades instead of the alleyway, the illumination helped direct patrons to local businesses, which was an important element in redefining the neighborhood’s narrative.

Additionally, local artists, selected by the community, were commissioned by a local business to create murals on the sides of the buildings flanking the alleyway. High-quality, wall-arm mounted, adjustable accent lights were focused on this art, honoring the local context and lending beauty and dignity to this once-unsafe alleyway. This strategic use of light has reduced some illicit activity in the alleyway, allowing more residents to feel safer to spend time outdoors in the evening hours.

Cultural Context Is Key

A comprehensive understanding of the cultural context is crucial for effective intervention. It is very important to understand both the problem and what exactly the light is being employed to solve. For instance, the aforementioned neighborhoods that house the Filipino Cultural District and Transgender District require respect for their heritage and an understanding of the socio-economic dynamics at play.

Situated directly across from the Jessie Street alleyway stands a historic hotel, repurposed as low-income, single-room occupancy housing. With a vast empty façade facing the Theatre District, the building had potential for adornment. Bonsignore, along with the OEWD, and SOMA Pilipinas, a local nonprofit, conceived the idea of embellishing this expansive wall with a captivating mural and reached out to artist Allison Hueman to commission artwork designed to pay homage to the rich Filipino history of the area. Drawing on her own Filipino roots, Hueman crafted a design that resonated with the culture and history of the residents of the area, transcending its role as a piece of art and serving as a gateway to the heart of the Filipino Cultural District of San Francisco.

The illumination of the mural utilized high-quality fixtures designed to withstand the test of time and the city’s often unpredictable weather. Meticulous attention was given to washing the entirety of the 50-ft wall evenly from the roof of the neighboring lower building, with a keen focus on glare control. Illuminating this culturally significant mural honors the rich history and importance of this neighborhood’s residents, restoring dignity, respect, and a sense of belonging. It connects the past with the present and future, preserving the legacy that continues to shape the community.

Practical Considerations

Implementing lighting projects in urban areas presents several practical challenges. From a technical standpoint, it is essential to ensure that the lighting design is suitable for the space without contributing to light pollution. Budget constraints and ongoing maintenance are also critical factors that must be carefully managed. Additionally, community involvement is vital to ensure that the solutions align with the needs and preferences of the area’s residents. When residents feel a sense of ownership of these installations, they are more likely to protect and maintain them, reducing the risk of vandalism. Engaging the community fosters pride and can significantly contribute to the long-term success of such initiatives. Achieving this requires effective outreach to the right stakeholders, including local residents, businesses, building owners, and agencies that may provide funding. While this outreach can be challenging—especially when it involves convincing multiple stakeholders— it is essential. Successfully engaging the community not only helps secure the necessary support but also revitalizes and strengthens urban neighborhoods, making them more vibrant and resilient.

Urban projects, such as these in San Francisco, are living experiments that provide valuable learning opportunities. Initially, designers may not always be equipped with the right questions, but over time, the importance of focusing on the community’s needs will become apparent. Designers can start by asking: What are the goals of the lighting design? What problems are we aiming to solve? Shifting the narrative from presumptive solutions to a problem-solving approach allows for the creation of more-effective and tailored solutions for the community.

For example, the luminaires along Jessie Street Alley encountered issues with vandalism shortly after installation. Within a day, one of the fixtures was broken, necessitating a reorder and a change in mounting location for all of the art lighting fixtures. To prevent further damage, these fixtures were relocated above the lower cornices, out of reach. While this new location was not ideal for illuminating the art on the walls below, it was a necessary compromise to preserve the installation.

The mural in the Filipino Cultural District also faced challenges related to the mounting location and power supply for the fixtures. Initially, after discussions with nearby building owners, permission was granted to mount fixtures on an adjacent lower building terrace and use power from that building. This location was optimal for the mural lighting, as there were no obstructions in the path of the light. However, as the project progressed, permission to mount on that building was revoked, forcing a relocation to a more distant building. This created significant challenges, as the optics of fixtures were optimized for the original mounting location. Additionally, the new location lacked a power source, necessitating a shift to solar power. This change required the purchase of solar panels and a battery system to complete the project successfully.

Many of these projects were funded by nonprofit organizations and/or private donors, often with “use it or lose it” clauses attached to the funding. These agreements necessitated early and accurate cost estimates for both labor and materials to optimize the use of available funds. In the projects mentioned, the funding organization, rather than the contractor, directly purchased the lighting fixtures. While this approach resulted in significant cost savings, it also required extensive coordination to ensure that all components were ordered correctly, with minimal input from the contractor and installer.

Working in urban neighborhoods also poses obstacles concerning safety during nighttime site visits. Although these areas may seem safer following lighting interventions, conducting pre-design night visits is crucial for understanding the social dynamics of the area. Surveying nearby neighborhoods is also necessary and often eye-opening. Even with a history of successfully managing urban projects, safety should always remain a key consideration in the planning and execution of similar projects in the future.

Urban challenges require complex, demanding, and nuanced solutions. While lighting alone is not a cure-all, it plays a critical role in revitalizing urban spaces. An understanding of what light can and cannot solve is very important while working on such initiatives. The projects in San Francisco demonstrate how targeted lighting initiatives can address specific urban issues, such as enhancing safety, lending aesthetics, fostering community pride, and improving economic activity. However, the effectiveness of lighting depends on understanding its limitations and integrating it into broader strategies that include social services, economic support, and community engagement. When combined with these elements, lighting can contribute significantly to the overall revitalization and cohesion of urban communities.

THE AUTHOR |

Neha Sivaprasad, LC, LEED AP, Member IES, IALD, is principal at Sol Light Studio.