Illumination, marine turtles, and the state of play

One of the current, and more interesting, corners of lighting is its interaction with nature. As we discuss the anthropogenic impacts of light on animals, it’s worth looking at marine turtles, which are easily one of the most studied interactions, and, unfortunately, one that remains poorly understood, poorly delivered, and poorly regulated.

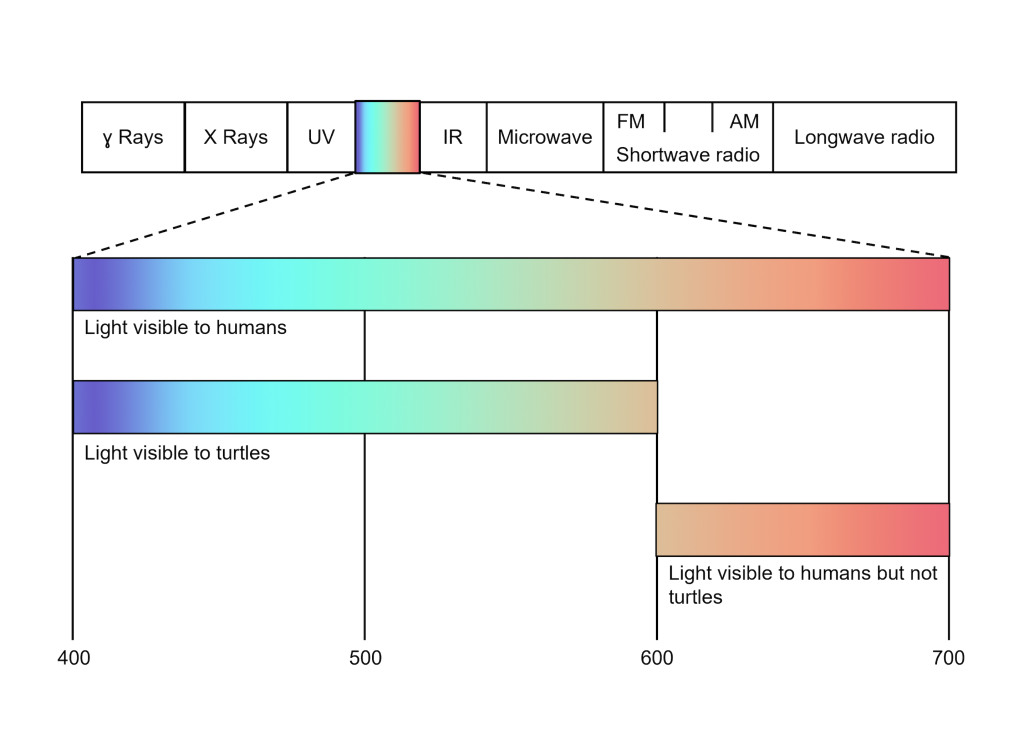

The basic biology of turtle vision is unusual because of where turtles use their eyes. Marine turtles are, technically speaking, amphibious mammals. This is to say, they hatch on land and race to the sea before predators can get them—and many years later, the females return to shore to nest. Essentially, the rest of their lives are lived in water, occasionally poking their heads out to breathe and, one presumes, look around. As a result of this dominant in-water life, turtles’ vision is optimized for life underwater. As every diver (and any avid adventure movie watcher) can tell you, it’s pretty blue down there. As one dives down through the first 10 meters (~33 ft), most of the red and orange light is absorbed by the water. By 20 meters (~66 ft), the limit of recreational open water diving, the world is dominated by the short end of the spectrum, blue and green wavelengths. Turtles’ eyes are optimized for this, and they’re essentially blind to red and amber light, sensitivity they simply don’t need.

This has been well established for many years and demonstrated in the wild by Blair Witherington and others in tests where beaches were lit with different wavelengths of light. In the sodium-lit areas, turtle behavior was unaffected as compared to unlit beaches.¹

That is what is popularly known, but there are other factors that are less studied. For example, another factor in the turtles’ environment is that they have minimal exposure to direct solar glare. Their eyes are optimized for life underwater, where the Sun’s rays are very much moderated. There is little research on the effects of glare on turtle vision and its ability to cause disorientation, but the precautionary principle would suggest that as lighting professionals, we should assume that turtles are distinctly vulnerable to glare.

Within the scientific community, there is a consensus that turtles are also disoriented at night by skyglow. The evidence for this appears solid on the surface, due to massive research by Florida Fish and Wildlife,² including surveys coordinated by Mote Marine Biology Laboratory³ and its volunteers and allied organizations. This appears to demonstrate that the majority of turtle disorientation events are due to skyglow. Unfortunately, this evidence is inferential and poorly collected. Without going into great detail, volunteers combing beaches every morning during the hatching season survey each disorientation event that happened during the night and fill in surveys that include presumed cause. It is unclear how volunteers might know whether skyglow was notably present the night before or whether it caused the disorientation; instead, it functions simply as a catch-all that cannot be proven. In contrast, there are also studies suggesting that the glow of clouds under moonlight and stars may be beneficial to turtle hatchling navigation; the still silhouette of tree lines and topography against the sky is actually used for navigation.

Turtles are nocturnal animals on land—they both nest and hatch during nighttime hours and are undoubtably vulnerable during that time. They are often demonstrably disoriented by street and house lights along beaches; the threat from artificial light is real. Though I have identified both understudied and overstated aspects of their engagement with light, one should assume (in absence of evidence to the contrary) that all light in their range of spectral sensitivity, to which they are exposed, is harmful.

Examining the State of the Art

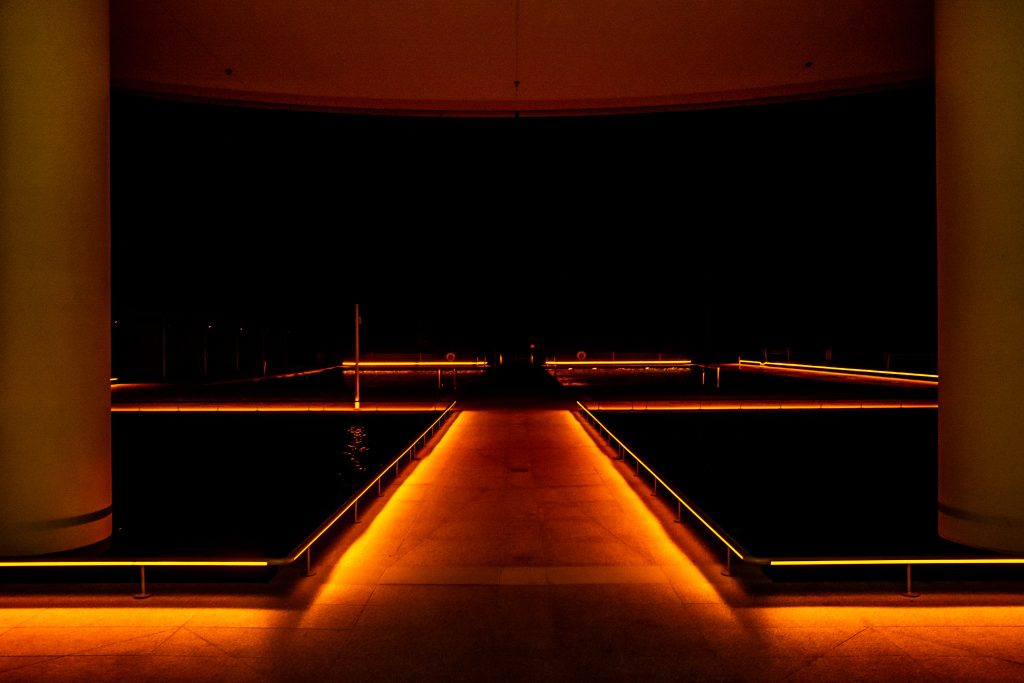

The state of the art for turtle lighting exists in three parts. Source technology in daily practice now consists essentially of LEDs—there’s no need to explore legacy fixture types. Native red and amber LEDs are monospectral and exist entirely outside of turtles’ spectral sensitivity. In principle, these sources can be used profligately without harm to turtles. That said, profligate use of light is rarely the right solution, and we should note that there may be other non-turtle species that are specifically sensitive in these ranges. Some reptiles, for example, have sensors in the near-infrared, and I’m unaware of studies demonstrating that their sensitivity doesn’t overlap with red LEDs. As such, the usual discretion should be applied in lighting with these sources.

From a design-aesthetic point of view, both red and amber LEDs have their downsides; being monospectral, they render the world in their own tone, black-and-amber or black-and-red, like a 1980s computer monitor. Blending the two can occasionally generate interesting results. Unfortunately, low CCT whites, which are occasionally mooted as options, cannot be considered as both contain shorter wavelengths that are visible to turtles.

I was involved with a project on which our team provided both proposed regulation and expert-witness work. We were peer reviewed by a large UK consultancy that claimed that RGB could also be used, if toned to warm colors—alas, this is incorrect. Any content in green or blue would be entirely visible to turtles, and the use of RGB fixtures set only to provide red would provide a point-of-failure should color settings be messed up, and no advantage over pure red.

The light that disorientates comes in essentially three groups. The first is direct source exposure—clearly this is unnecessary and harmful—shielding of all direct source views should be considered essential around marine turtle nesting grounds. Heck, it should be considered baseline around humans! The second type of light exposure is the visibility of lit surfaces by turtles—that is to say, if one washes a wall with light, uplights a tree, or otherwise lights a surface, it potentially disorients a turtle, if in their visible spectrum.

Finally, skyglow or indirect atmospheric scatter such as fog, mist, clouds, and rainfall are potential sources of view to light sources from turtles. As previously noted, the evidence that this is problematic is marginal at best. On the other hand, skyglow is harmful to many other species including insects, birds, bats, and humans, so we should be careful to control and manage skyglow whatever the level of certainty of impact on turtles.

The shielding and management of mounting heights is very low-tech but is a key part of any solution to turtle lighting. Simply orienting all lighting away from the beach and using honeycomb louvers, deep snoots, and beach-side shields is easy to do and provides an immediate payoff.

The State of the Law Versus Turtle Needs

The state of the law is a vast distance from the real needs of turtles. Regulations fall into three buckets, all of which fail to be fit-for-purpose. They are written by turtle experts, not lighting experts, and it shows.

- The State of Florida Model Lighting Ordinance (FMLO) for Sea Turtle Protection: The FMLO⁴ in its many adoptions in Florida counties, and far beyond, is a mess. The document was written by marine biologists with little understanding of lighting, less of code compliance, and a complete failure to look at the turtles’ umwelt. It treats all downward-facing lighting as better, but almost every source it recommends is essentially directly visible from a turtle’s eye at 6 in. above the sand or water. Turtles’ eyes are down from any source other than an uplight. Due to the extreme height constraints applied in this code and the options it permits, it regularly leads to massive over-lighting—not because it requires it, but its interaction with egress and emergency lighting requirements become onerous. It also encourages horizontal-throw luminaires, which essentially puts light on the turtles’ eyelines and throws long distances. For example, to light to 3 footcandles around a hotel swimming pool by the beach, from a few inches above the deck surface, an enormous density of fixtures is required—similarly with path lighting.

The document is not fit-for-purpose, but no substantive review has been performed involving serious lighting designers positing viable solutions. As such, assume that such lighting will be problematic. My advice within variants of this law is simple: follow it and do it the leastworst you can. Over-light as needs to meet code, then pare back after your inspections, where professionally judged appropriate. Circuit 80% of the light as emergency-only in reality, if not on drawings. - Australian Regulations: Australia has been leading the way on appropriate models of turtle lighting.⁵ In my professional practice, I have not had the opportunity to apply or review such lighting. I’m excited to do so on forthcoming projects, but for now, my advice is to read these regulations and understand their purpose and methods.

- European Legislation: European legislation is a hodgepodge of national standards (and their absence) under an overarching principle that anthropogenic lighting should be mitigated where it impinges on the natural environment. In principle, this gives a lot of freedom to designers to use their own initiative to develop siteappropriate solutions that appropriately mitigate the impact on sea turtles. In practice, it’s nebulous, hard to deliver, and harder to demonstrate. European legislation is particularly vulnerable to nuisance assertions of insufficient mitigation by third parties since the question of what is sufficient mitigation is left to judgment.

- DarkSky: DarkSky recently published a new model ordinance,⁶ which replaces its old collaboration with the IES. The ordinance is often mooted as appropriate for turtle environments, however, the main document is primarily focused on fugitive light upwards, rather than addressing the experience of the eye below that level. In the past, we often cherry-picked useful parts of the previous version for turtle protection, but the new version is lightweight with regard to downward light and contributes little to a problem that is primarily downward-facing. The supplementary text that DarkSky proposes for its model ordinance in the context of turtles is insufficient, unclear, and ineffective in providing deliverable direction for lighting. The general guidelines limit downward fugitive light, treating it as a question of quantification of glare (BUG rating) rather than a concealment problem. We must assume that for turtles’ eyes, any glare/source view of a spectrum they can see is too much. DarkSky’s goal of warm-white light is appropriate for humans but is not specific enough for sea turtles—the low CCT may be heavy on long spectra, but the source-view contains shorter wavelengths, too—and from typically compact, glary sources for turtles’ eyes. The addition of the turtle supplement then limits light to 0.1 lux, irrespective of wavelength. This last term is odd, as it creates impossible implications for egress lighting from properties by the beach, for example—or nearby parking lots. The pole height requirements are arbitrary and allow luminaires to be located well over turtles’ heads but still limits the ability to use structure-mounted lights oriented away from the beach to best light areas. Strangely, it emphasizes low-pressure sodium as a reference source, where amber and red LEDs would be more realistic and appropriate in 2025. My practice has a policy of observing DarkSky in environmentally sensitive environments, but it is not fit-for-purpose as a catchall for turtles. More specific text is required.

Questions and Context

Unfortunately, there is a structural problem in the application of environmental laws to turtle protection. Specifically, we have seen that organizations protesting a development, in general, can simply assert that lighting methodologies are not sufficiently mitigating of lighting for turtles, thereby blocking the whole development. What is mitigation regarding impact on turtles? What is considered sufficient? Where are the limits to which it applies? These questions are too vague for effective evaluation by courts that do not include sufficient professionals in their judging panels. We have seen several projects entirely frozen by turtle-related complaints, and it’s become increasingly clear that it’s simply the easiest stick with which to beat the project, even when disingenuous.

Working in this context, it is important to provide not only effective solutions but also graphical and analytical methodology statements that can be communicated to interested parties. Putting turtle protection strategies into the public domain and showing how easily their success can be demonstrated becomes key. I recommend some simple language to be used wherever true and appropriate: “The proposed lighting shall be subject to final evaluation by eye. Any viewer, on the beach up to the first dune or in the water approaches, shall be unable to see any light source or substantially lit surface in any light source other than amber or red. Should this be breached, the owner shall be liable for immediate rectification.”

Now you need to design to meet it.

What Should We Do?

A simple thought experiment should help you work out genuinely turtle-appropriate lighting. Always remember that turtles’ eyes are rarely more than 6 in. above the sand, and less than that above the water. Consider everywhere a turtle might be: wavetop at high tide or crawling up to the first dune. From those vantage points, what can they see? If they can’t see a surface you’re lighting or the light source, then you’re well sorted. Even better is if you can do everything that might light mist, rain, fog, etc., in the visible area above your site in amber or red LEDs—then you’ve really addressed the turtles’ needs. So, shield heavily, select lit surfaces carefully, spectra with care, and the turtles will be fine.

I also suggest installing fixtures higher rather than lower since they will be more effective and more easily shielded/directed—every time you use an 18-in. path light, to get egress coverage, you’ll either be throwing as wide as you can (near 180-deg/batwing) or have a huge density of sources—all of which the turtles’ eyes are looking up and across into. Don’t be afraid to pole/façade mounts and light down with carefully selected and shielded area lights, spot lights, accents, and under-handrail lights. Be sure to throw away from the beach wherever possible, to conceal the faces of luminaires.

Circuit everything for seasonality. Having a nesting/hatching season turn-down for your lighting, inside and out, is a great way to genuinely benefit the turtles, while limiting human use of the space only during certain seasons.

We often offer portable lighting to our clients for their beachside landscapes. In the past, we’ve done this with kerosene torches, battery lamps, or in one spectacular case, interior sconces at exits that can be lifted off their mounts and converted into battery lanterns.

What to Avoid?

Path lights, floodlights, step lights, and stair nosings all have their problems. Though a stair nosing light might seem clever, one typically illuminates the riser heavily, and that’s a lot of light if you are reaching egress standards even one tread out from the source. Use your imagination about where there will be hotspots. Area lights such as pole fixtures are fine—great, if you can use house-sideshields to shield through greater than 180 deg toward the beach. But avoid anything in white, that which can’t be heavily shielded, and anything that is self-lighting—white or metallic poles that catch light from the head, for example.

Balconies on buildings really don’t need a lot of light, and downlights, sconces, or step lights must appear phantasmagorical to hatching turtles, hovering 15 stories over Miami beach. If you really need to light these areas, put the fixture in the handrail lighting 100% inwards; if anyone is going to feel the glare, it can be the owner. Interior lighting isn’t covered by most codes, and you can’t really tell clients that you are not going to light their interiors, so do light them. I recommend having blackout shades that automatically close after sunset; they can always be opened manually, if need be, but if you have an entire hotel façade blacked out and 5% decide to open their shades, that’s a huge benefit.

Is it worth all the cost and complexity of lighting for turtles? And does it work? Absolutely. The Florida west coast, where turtle lighting ordinances have the longest track record and strongest enforcement, is now seeing nesting populations bouncing back after a quarter century of dedication. This does work. It can get better. Join me in protecting the turtles.

THE AUTHOR |

Thomas Paterson is the founder and director of Lux Populi.

References

- ¹ Blair E. Witherington, “Behavioral Responses of Nesting Sea Turtles to Artificial Lighting,” Herpetologica, vol. 48, no. 1, Mar. 1992.

- ² Blair E. Witherington, R. Erik Martin, and Robbin N. Trindell, “Understanding, Assessing, and Resolving Light-Pollution Problems on Sea Turtle Nesting Beaches,” Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, 2014.

- ³ Mote Marine Laboratory and Aquarium, “Conservation, Restoration and Monitoring,” 2025. Available: https://mote.org/research/programs/areas-of-research/conservation-restorationmonitoring/

- ⁴ Florida Department of Environmental Protection, “The State of Florida Model Lighting Ordinance (FMLO) for Sea Turtle Protection,” Dec. 17, 2020. Available: https://floridadep.gov/sites/default/files/62B-55_ModelLightingOrdinance_NPR_0.pdf

- ⁵ State of Queensland, Department of State Development, Manufacturing, Infrastructure, and Planning, “Sea Turtle Sensitive Area Code: A Model Code for Local Government,” May 2019. Available: https://dsdmipprd.blob.core.windows.net/general/sea-turtle-sensitive-area-code.pdf

- ⁶ DarkSky, “Outdoor Lighting—Coastal Marine Turtle Supplement,” Oct. 11, 2024. Available: https://darksky.app.box.com/s/l45i775cxjqgc2o36vap9qh62blvpgdk