A combination of educational resources, cutting-edge technology, specifier buy-in and community involvement can protect the night sky

The words “summer night” call to mind a distinct set of happenings in the natural world. Crickets sound their nightly chorus in darkened yards and thickets, fireflies flash their whereabouts, moths pollinate the garden and bats hunt mosquitoes overhead. Meanwhile, on coastal beaches, sea turtle hatchlings await the cool of nighttime before emerging from sandy nests and scrambling toward the shore.

Humans have nocturnal habits characteristic of the season, too. We stay outside long after sunset for sporting events, backyard barbeques and outdoor dining—all under the glow of artificial lights. Some seek out patches of darkness to scan the sky for constellations, planets and shooting stars.

But views of the night sky are increasingly obscured by illuminated buildings, parks and streets, particularly in urban areas. And when we eventually go to sleep in darkened homes, the outdoor lights of houses and apartment buildings, yards and roadways often remain on until dawn—unintentionally disrupting nature’s rhythms of the night. Light pollution is a problem that is accelerating by about 10% per year, according to the World Atlas of Artificial Night Sky Brightness, causing more than a third of Earth’s population—including 60% of Europeans and nearly 80% of North Americans—to lose their ability to see the Milky Way.

For other creatures, the impacts of light pollution are much worse. As they have for millennia, wildlife species rely on the natural cadence of the sun and moon to thrive. When nighttime illumination from buildings, streetlights and parking lots interrupts those natural cycles, it impairs behaviors that have evolved over millions of years, affecting species from insects and birds to reptiles and mammals, and disrupting behaviors such as migration, foraging and mating.

Birds, for example, migrate mainly at night. Illuminated buildings disorient them and are a significant hazard. An estimated 365 million to 988 million birds die in collisions with buildings annually, according to Cornell University’s BirdCast program, which urges cities and other building owners to extinguish or dim outdoor lighting during fall and spring migration. Prominent examples of light pollution impacts include the deaths of hundreds of birds in a single night in New York City, 1,000 to 1,500 birds dead in one night in Philadelphia, and about 400 migrating birds killed colliding with a single building in Galveston, TX. Attraction to artificial light can also cause birds to continuously circle in cones of brightness until they become exhausted and descend to the ground. Once downed, they are easy targets for automobiles and predators. At a forum in Honolulu last February, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service reported rescuing over 1,200 fledgling seabirds between 2020 and 2021, and over 900 in 2022, descended from the night sky after being “trapped” in artificial lights.

Hosted by Hawaii Energy, the DesignLights Consortium (DLC) and the IES Honolulu Section, the February panel discussion covered topics such as how outdoor lighting affects coastal ecosystems (including migrating birds) and astronomical study, as well as resources that municipalities, building owners and other outdoor lighting decision makers can use to reduce negative impacts such as sky glow (unnatural brightening of the night sky) and light trespass (light shining where it’s not wanted or needed). Among the resources discussed were the DLC’s LUNA Technical Requirements and accompanying Qualified Products List (QPL), which identifies and promotes energy efficient luminaires that adhere to responsible outdoor lighting principles. Among other things, LUNA requires that qualified products be controlled with timers, motion detectors and other technology that allows them to dim or turn off when not needed—preventatives to inadvertent all-night lighting.

The panel also highlighted the need for collaboration and coordination among various scientific disciplines and the lighting industry to address mounting conflicts between human needs for outdoor recreation and safety and the need to protect darkness for wildlife habitats, biodiversity and astronomical research. Faced with statistics like the fact that light pollution is the third highest threat to viability for fireflies and pollinating insects, the issue is increasingly bringing together academic and government agency biologists to share research and work toward solutions that balance society’s reliance on quality outdoor lighting with the important function darkness plays in the lives of all living things.

The February event also addressed the financial costs and carbon emissions associated with light pollution. According to the International Dark-Sky Association (IDA), a third of all outdoor lighting in the U.S. is wasted, costing facility owners some $3.3 billion annually and responsible for 21 million tons of needless carbon emissions annually.

Graceson Ghen of Hawaii Energy’s Energy Efficiency Program noted that the Big Island was an early adopter of light pollution protections, enacting an ordinance in 1989 to limit the impacts. Known as Article 9, the regulation worked well while low-pressure sodium lighting dominated the outdoor lighting landscape, but the arrival of LEDs with their brighter, blue-hued light required a new solution. In 2013, the county began a project ries and over 275 North American counties and municipalities have light pollution mitigation laws or ordinances of some sort in place. The DLC hosts a list of the U.S. bylaws and ordinances for lighting specifiers to inform their projects.

Lighting ordinances are one of several effective strategies for mitigating the unintended impacts of outdoor lighting. The DLC’s recently-published “Responsible Light at Night for Local Governments” is a collection of online resources designed to guide public-sector decision makers in establishing the most appropriate lighting policies in their communities. The online toolkit references the LUNA Technical Requirements, pointing local lighting projects toward fixtures that meet independently vetted light pollution mitigation criteria while also achieving energy efficiency and other performance benchmarks.

Products on the LUNA QPL meet the energy savings and lighting quality benchmarks of the DLC’s Solid-State Lighting Technical Requirements, as well as attributes that limit sky glow and light trespass. Selecting LUNA-qualified products can help municipalities, private facilities and other outdoor lighting decision makers better support their energy reduction goals and abide by local dark-sky policies and ordinances. LUNA also helps specifiers fulfill the light pollution and trespass requirements of LEED and WELL building programs, and helps projects follow application guidance in the IES Model Lighting Ordinance.

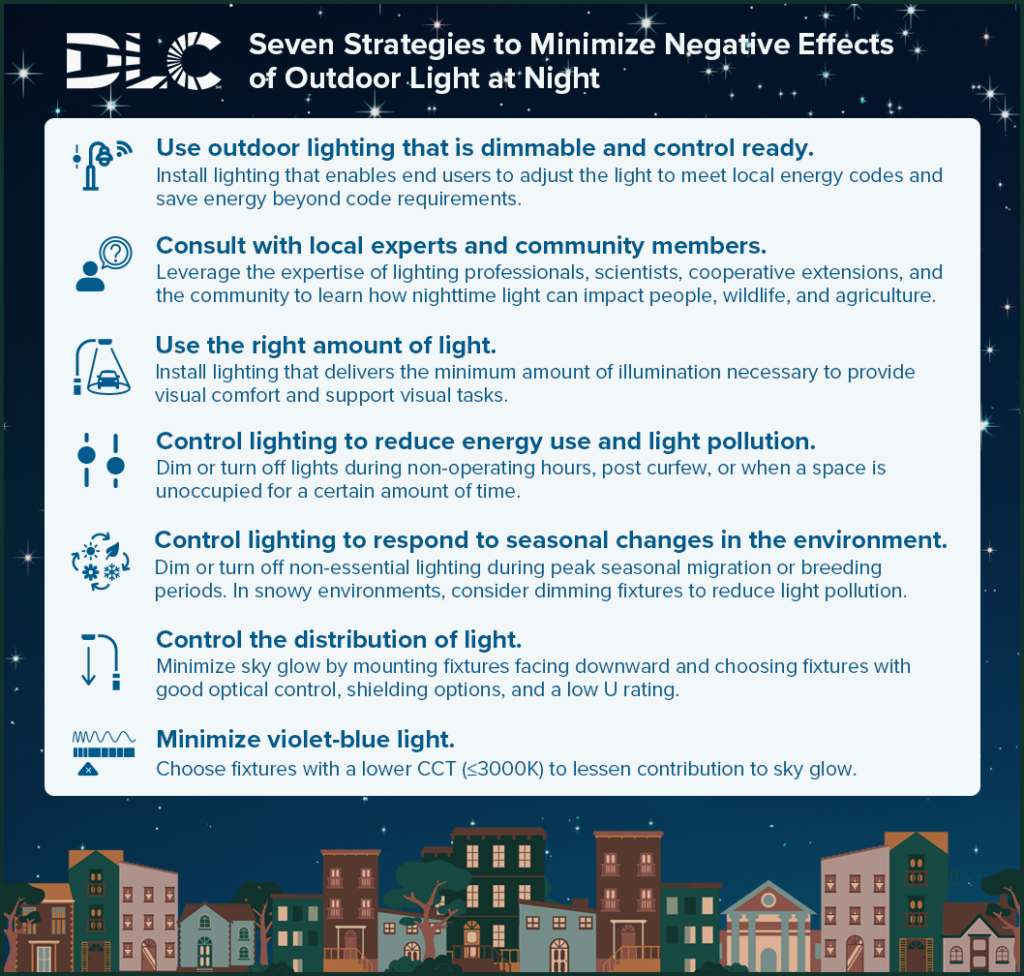

While LUNA is an important way to aim the lighting market toward products that mitigate light pollution, the policy does not yet cover all outdoor LED products. Although research has shown that non-white light (“amber”) LEDs are safer options for some wildlife species, the DLC does not allow non-white light products to be qualified under LUNA due to lack of standards for this technology. A paper co-authored by DLC Senior Lighting Scientist Leora Radetsky and published in LEUKOS, the Journal of the Illuminating Engineering Society, in January proposes a specification structure for amber light sources and encourages lighting standards development organizations to create standards to eliminate inconsistencies with product claims. The DLC has also published a whitepaper on non-white light in outdoor environments and a related FAQ, and is closely monitoring progress on this front. Use of warmer amber lights, where appropriate and possible, is among seven strategies the DLC has published to guide planners and developers of outdoor lighting projects (Table 1). Finally, increasing the number of available products designed to cut light pollution would go a long way toward ensuring that lighting for road ways, building façades, parks and other outdoor spaces is energy efficient and doesn’t compromise the natural night sky.

Speaking recently with the DLC about the impacts of light pollution on human communities, particularly historically disenfranchised neighborhoods, Lauren Dandridge, principal of the lighting design firm Chromatic, and Don Slater, associate professor of sociology at the London School of Economics and Political Science, urged a larger role for lighting manufacturers. Commenting in a March DLC blog article, Dandridge predicted that more interest in light pollution mitigation on the part of manufacturers “would be a game-changer.” Because municipalities view lighting more as a commodity than an agent of environmental quality, they are apt to go directly to manufacturers to get the best deal for large quantities of fixtures for streetlights, parks and other projects, rather than prioritize the advice of experts in lighting design. “If manufacturers took this under their wing,” Dandridge said, change would happen faster.

Outdoor lighting is a permanent fixture in our 24/7 society, allowing for gathering and recreation past daytime hours and enabling visibility for better mobility at night. But growing evidence points to myriad ways artificial light can harm wildlife, hinder astronomical study and disrupt the comfort of hu man communities. As various scientific disciplines, segments of the lighting industry, and public and private sector lighting decision makers increasingly learn and collaborate, we can and must tackle this challenge with practical solutions that yield co-benefits for environmental sustainability, human well-being and energy costs.