The evolution of human-centric lighting

Earlier this year, I stood with my son beneath the dome of the Pantheon in Rome. As daylight beamed down through the oculus, we were filled with awe, just as countless others have been for more than two millennia. The temple’s ancient designers understood that light can do more than illuminate; it can evoke emotion, create a sense of place and enhance well-being.

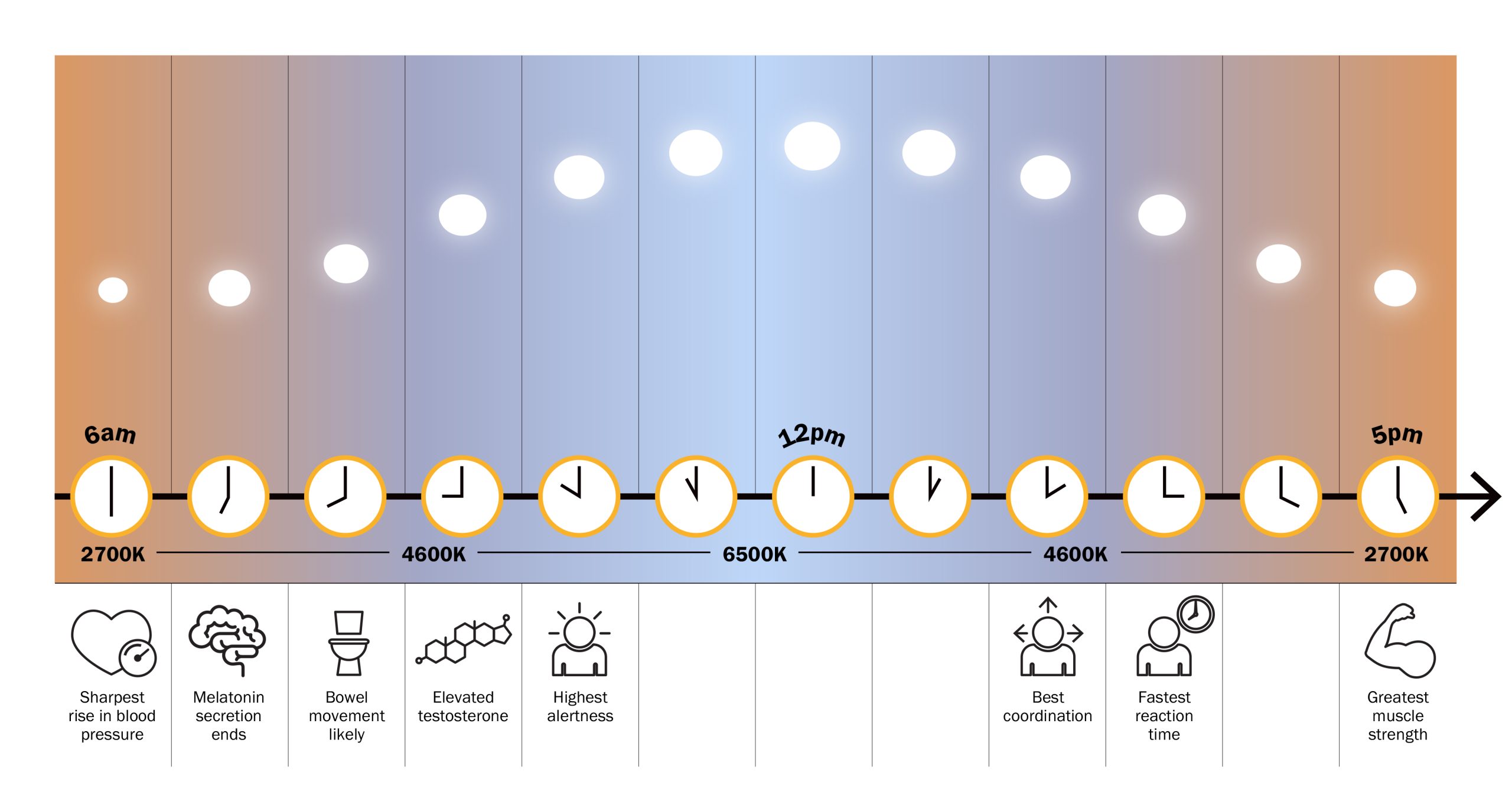

Centuries later, with our advanced lighting technology, there is a renewed focus on those age-old principles and how modern lighting practices can transcend simple visibility. While material costs, energy use, and efficiency requirements are often still the main drivers of lighting design, more emphasis than ever before is being placed on how humans experience designed lighting. The modern concept of human-centric lighting (HCL) focuses on how light affects our vision, physiology, and psychology. Lighting for circadian entrainment is a key aspect, but the concept also encompasses light’s broader influences, such as hormone production, mood, sleep regulation, and cognitive function. By considering these effects along with visual quality and aesthetics, HCL aims to enhance overall well-being, leveraging modern research to address the impact of today’s advanced lighting technologies.

Throughout history, humans have instinctively used light to improve well-being. Consider the use of firelight in public and domestic spaces. The warm, flickering light of communal fires and hearths not only provided warmth and visibility but also transformed these spaces into inviting centers where people could gather in comfort after dark. This early use of light was not merely practical—it inherently addressed the human experience by creating environments that fostered social cohesion and psychological well-being.

Light has also played a crucial role in cultural and religious rituals, particularly during the darkest times of the year. Across various traditions, the use of light—whether from oil lamps, candles, or bonfires—has symbolized hope and renewal. By illuminating the darkness, these practices uplifted spirits and helped communities navigate the emotional challenges of long, dark winters. These were precursors to our modern understanding of light’s impact on mood and biological cycles.

As societies grew, early street lighting, from modest candle-lit windows to the eventual use of oil and gas lamps, did more than just illuminate the streets—it encouraged social interaction and extended public life into the evening hours. A newfound sense of improved safety, whether real or perceived, played a crucial role in how communities engaged with their environment after dark, further highlighting light’s ability to shape human behavior and comfort.

It’s notable that most pre-electric lighting was a form of flame. While this light did have some impact on people’s waking hours, the sources emitted warm light with minimal short wavelengths, which had little to no impact on circadian entrainment.

This allowed for a natural alignment with human biological cycles, in contrast to the disruptions that can be caused by modern electric lighting. As electric lighting became widespread in the early 20th century, it revolutionized how light influenced people’s daily lives in positive and negative ways. The illuminated environment extended the useful day, but it also began to diverge from natural patterns of light, causing more impact on human systems.

Interest in how light affects people began to grow. In the 1920s and 1930s, early studies explored how lighting conditions went beyond visibility to influence worker satisfaction and productivity. In the 1940s and 1950s, research focused on how light exposure can regulate the body’s biological cycles. The term “circadian” was coined, laying the foundation for recognizing how light influences sleep, mood, and overall health. From the 1960s through the 1980s, research into the psychological impact of lighting showed that bright, cool light enhances alertness, while dim, warm light promotes relaxation.

In recent decades, the field of photobiology has seen significant progress. In 1998, melanopsin, a photopigment in the retina sensitive to blue light, was discovered. In 2002, researchers proved the existence of intrinsically photosensitive retinal ganglion cells. These play a crucial role in regulating circadian rhythms using melanopsin. Additional work by researchers such as Dr. George Brainard highlights the impact of specific light wavelengths on melatonin regulation. These discoveries have profoundly changed our understanding of light’s effects on humans.

Today, building on historical uses of light for comfort and social interaction, informed by scientific research, and facilitated by LED technology and advanced controls, HCL systems are increasingly applied in the built environment to optimize people’s well-being and quality of life. While efficiency and cost are still major drivers, there is a broad cultural movement toward creating environments that prioritize human experience.

Launched in 2013, the WELL Building Standard was a key catalyst in raising awareness of HCL. By addressing the human circadian response to lighting, it helped remind the design community that we light spaces for people, not just to meet codes. “Circadian lighting” is now regularly integrated into projects. Just as daylight shifting to the warm glow of pre-electric light sources aligned naturally with human biology, modern systems can adjust the spectrum of light in a space to mimic these natural patterns, supporting circadian rhythms, enhancing alertness, and aiding relaxation throughout the day.

Across all sectors, HCL can have positive impacts. In workplaces, this understanding can translate to increased productivity and reduced fatigue, while in healthcare settings, it supports patient recovery by regulating sleep-wake cycles and reduces stress for night-shift workers. Educational environments benefit from lighting that can enhance focus during lessons and create calming spaces for creativity.

Outdoor spaces, like modern parks, can use HCL approaches to create comfortable communal gathering places after dark. These spaces echo the historic role of central gathering areas illuminated by firelight places where people came together for safety, social interaction, and community. New parks continue this tradition by using innovative lighting designs to transform public spaces into gathering hubs, ensuring they are just as welcoming and functional at night as they are during the day.

HCL still has its hurdles. While interest is growing, its adoption is still expanding as the industry navigates challenges related to cost, standardization, and education. Many questions about how humans respond to light also remain unanswered. For example, how might exposure to specific wavelengths of light influence our psychology, long-term cognitive function, eye health, or even immune responses? How can we optimize the interplay of daylight and electric light to reduce stress more effectively? Could the light-based experiences people universally find beautiful, such as sunsets or the sparkle of sunlight on water, be loved because they affect us biologically as well as visually? As research progresses and our understanding of light’s non-visual effects deepens, we stand on the brink of a new era in lighting design.

Like the architects of the Pantheon, who used light to transcend the visual, modern designers are building on instinctive practices with the critical addition of scientific data. As our understanding of light continues to evolve, we have the opportunity to create environments that are functional and aesthetically pleasing as well as deeply supportive of human well-being.